It’s easy enough to find your home router’s public facing IP address (the one your ISP assigns) via a Google search; they even make it the first result on the page. But what if you want to find it via a script?

That’s the challenge I’m trying to solve. What’s more, I want to do this without calling something on an external service. I’ll only be looking it up once every five minutes or so, but I’d prefer to not be a nuisance. (And if something goes wrong and my script runs in a tight loop, I’d rather not have the polling hammer someone else’s server.)

I found a script on the Linux & Things blog which almost does what I want. That script doesn’t quite work for me though, my route command doesn’t flag the default gateway.

But that’s OK, the bulk of what that script does is to look up the local network’s name for the router. That’s a nice bit of robustness, just in case the router’s name does change for some reason (e.g. switching from Fios to Comcast, you’d get a new router and the new router would likely have a different default name). But for my purposes, it’s good enough to know that the router’s name is always going to be Fred. (No, not really, that would be silly. My router’s real name is Ethel.)

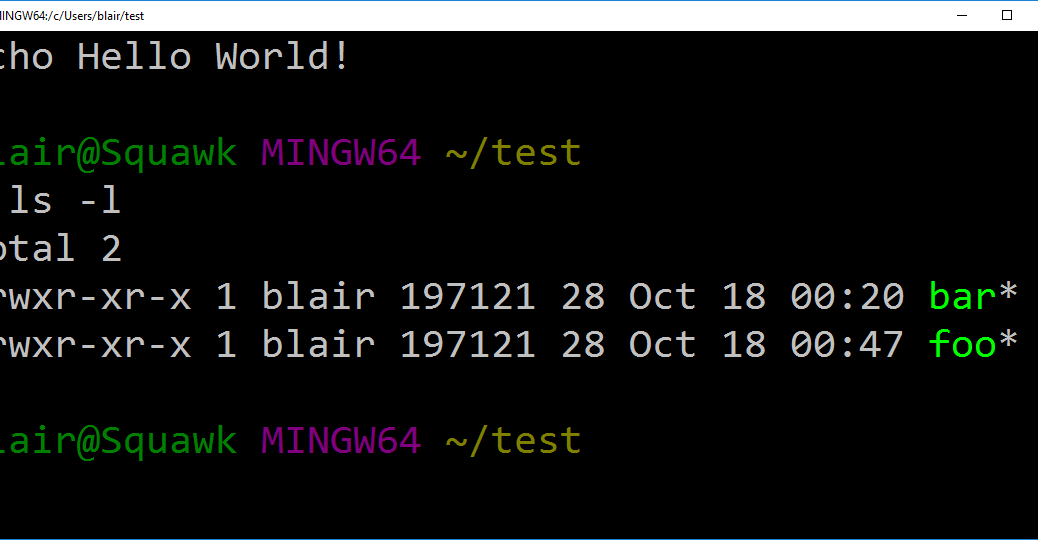

So from a bash prompt, we end up with this snippet of code:

That one-liner really breaks down to five parts.

nslookup Fred.home looks up Fred’s entry in the local DNS. What I get is something similar to:

Address: 192.168.1.1#53

Name: Fred.home

Address: 192.168.1.1

Name: Fred.home

Address: 172.217.8.14

Now none of that’s my real network information, but what we’re after is that last “Address” line.

Piping the output of nslookup through grep Address throws away every line which doesn’t contain the word “Address”, leaving this:

Address: 192.168.1.1

Address: 172.217.8.14

Getting closer, next, it gets piped through tail -1 which grabs just the last line:

Excellent! That’s almost what we want.

The next step in the chain is to run it through awk '{print $2}' which uses the AWK tool to output just the second token in the stream.

Finally, the entire thing is wrapped in the $() operator, which captures the output of those four steps and allows us to assign them to the

external_address

variable, which allows the external address to be used elsewhere:

echo $external_address

172.217.8.14

This (obviously) runs at a bash prompt. I’ve tried it out on Ubuntu and the Windows Subsystem for Linux, though I can’t imagine it wouldn’t work on other distributions as well. Most of the magic in this is text parsing. The Windows version of nslookup provides similar output, just formatted differently; there’s no reason a PowerShell script couldn’t do some similar processing to find the address.